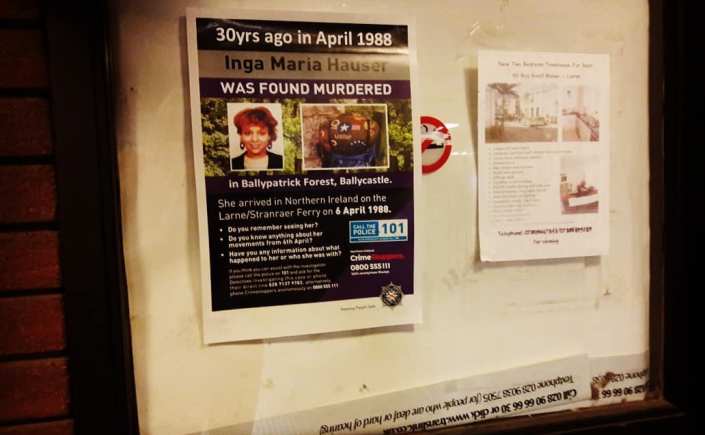

The definitive account of the only case of its kind, a search for truth and a labour-of-love in memory of the victim of a unique murder mystery still officially unsolved 33 years on

By Keeley Moss

PART 34 – CONTENTS

Chapter 89: Nowhere

Chapter 90: One Step Closer to Knowing

Chapter 91: A Lift from Larne

Acknowledgements for Part 34

Chapter 89: Nowhere

All that’s left is you and me and here we are nowhere

Ride – ‘Nowhere’

For anyone who hasn’t been following the previous 13 instalments of this blog, this is the next stage of my retracing Inga’s movements by undertaking a solo backpacking trip on an Interrail pass through England, Scotland and the north (and south) of Ireland for the purpose of researching my book about Inga and her case (which is a separate work to this blog) and to keep her memory alive by trying to complete the journey that she was so tragically murdered in the process of undertaking. I am also doing this in order to show just how far she travelled and the sheer effort she made to get where she was going before she was killed, a very important aspect of Inga’s legacy that was overlooked for too long. She came so far. So near and yet, so far…

My mum, who like surely almost all Irish mothers is very much a worrier, had spent much of the week prior to my departure from Dublin for the four-day trip retracing Inga’s steps around the UK getting me to promise her that whatever happened, I would not accept a lift in Larne. And every time she said this, I scoffed. I couldn’t help thinking it was the most ridiculous idea in the world. For one thing, I thought that the chance of lightning striking twice at Larne ferry terminal was so incredibly unlikely as to be near enough unthinkable.

Secondly, having spent literally every day of the last four years immersed in the details of this case, if anyone was going to be mindful of the dangers of taking a lift from Larne ferry terminal it would surely be me. My life revolves around writing and campaigning about someone who was murdered after accepting a lift from Larne, so I considered myself the last person on the planet who would do the same thing. I’m ordinarily gung-ho enough to take the chance were it offered elsewhere but given the nature of my involvement in this case, the thought of my being offered a lift from Larne let alone accepting such an offer sounded so far-fetched to me that I couldn’t help but laugh out loud at the thought that anyone might think it even a possibility. It was the last thing in the world I would do.

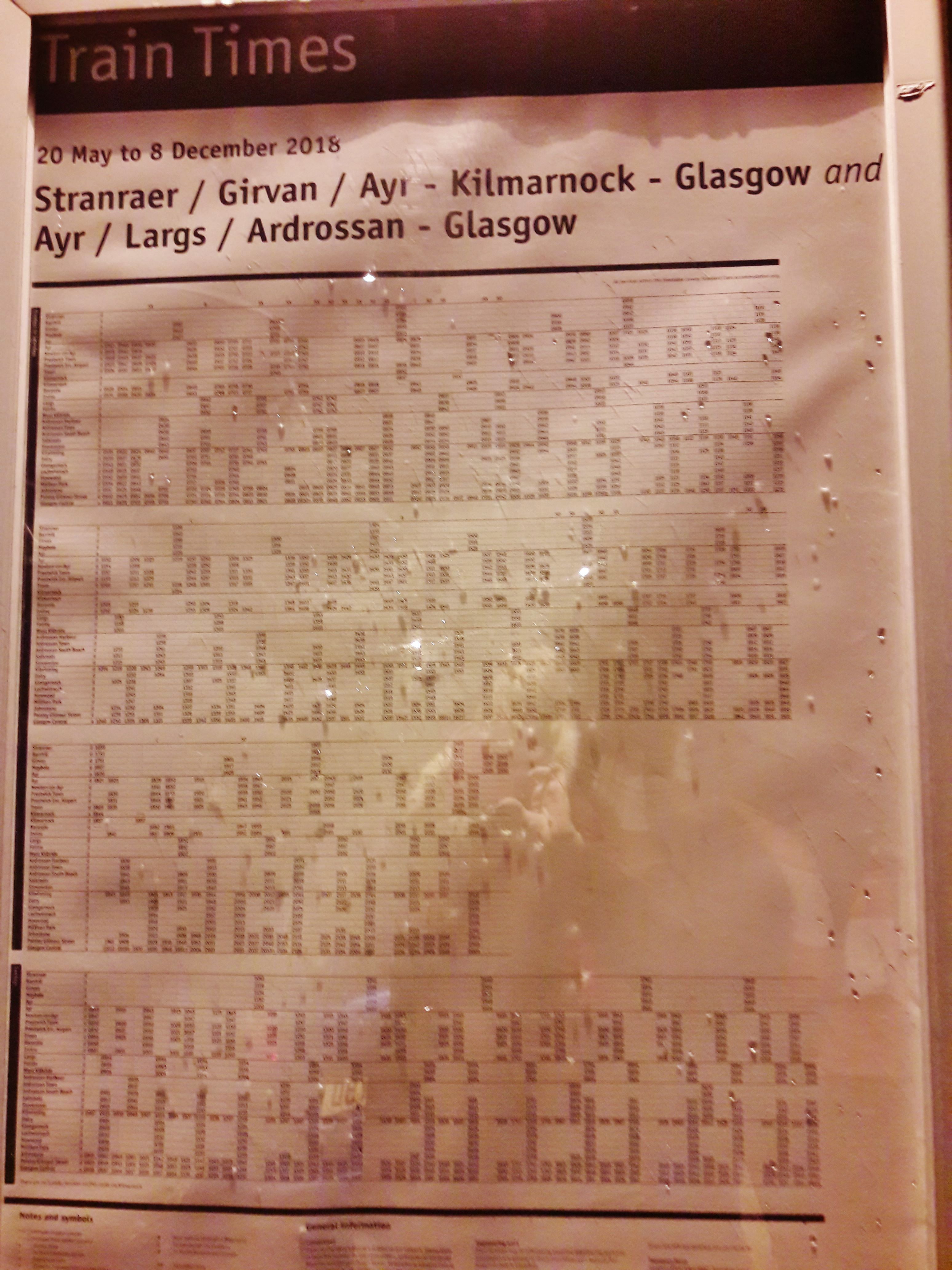

Besides, I was intent on making sure that there was only one way I would be leaving Larne this night – on a train. The same train journey Inga should have been on. It was the centrepiece of this spiritual mission. That is not to negate how much the previous four days of this backpacking trip had meant to me but getting to go one step beyond and make my next steps of the journey from Scotland to Larne Harbour by ferry, on to Belfast by train and then onto Dublin as had been Inga’s original intention, was so important to me.

But because the last train had inexplicably left Larne Harbour train station a whole hour before my arrival on the last ferry of the night from Scotland, and there were no more trains, and no buses, and no taxis anywhere in Larne tonight (see Part 33), I was stranded.

The only other person in the terminal besides me at this point, a woman I had met only a few minutes before amid frankly eerie circumstances, Fiona, phoned a friend of hers who she told about our predicament. And this friend had offered to drive up here and give us a lift to Belfast. Great. A lift from Larne. To Belfast. An offer that was extended to me. What could possibly go wrong? All I had to do was trust them.

This was identical to the situation Inga was faced with in the very same building 30 years prior to my retracing her footsteps this far.

I could not believe this was happening.

This could’ve happened in any one of the dozen or so stations where I had retraced Inga’s steps in London. Or it could have happened when I went to Headington. Or Oxford. Or Bath. Or Bristol. Or Preston. Or Inverness. Or in either of the two stations in Glasgow. Or Ayr. Or Stranraer. And it wouldn’t have been strange. But given the history of the case and the circumstances of why I was here, for this to happen in Larne?

I stood still, stunned.

What was I to do? Should I stay or should I go? This is the night I learned that Larne really is a ghost town, it makes my native Dublin look like New York by comparison.

No trains. No buses. No taxis.

Nowhere.

Chapter 90: One Step Closer to Knowing

Two ways to choose

On a razor’s edge

Remain behind

Go straight aheadTwo ways to choose

Which way to go?

Had thoughts for one

Designs for bothI see your face still in my window

Torments yet calms, won’t set me freeJoy Division – ‘Something Must Break’

Lost in my thoughts I didn’t hear Fiona say something. I looked up from the seat where I was sitting in the empty waiting area of the ferry terminal. “Are you coming with us or not?” she was saying. Her friend was about to pull up in a car outside apparently. But who were “they”? Were they a he or a she? Or a he and a she? And either way, would it really make a difference? At separate times, and for a very long time, detectives from the RUC, detectives from the An Garda Siochana taskforce Operation Trace who re-investigated Inga’s case (to the obliviousness of the media at the time) and latterly PSNI investigators all for a time favoured a theory that on the night Inga was murdered, she must have had a good reason to have set aside all of her inhibitions in accepting a lift from Larne (Inga was categorically not a hitchhiker as the media have frequently misreported over the years, she had not once taken a lift with anyone at any point during her week-long trek through the UK, until the night she arrived in Larne).

One of the most popular theories as to what that reason may have been, shared at various times by a number of detectives across each of the separate investigation teams, was that perhaps there may have been an additional passenger in the vehicle that Inga left Larne in, such as a woman or an elderly grandfather-type figure, someone whose presence Inga would have undoubtedly found reassuring. In a case where as I have seen many times over the past four years, and indeed having painstakingly pored over 32 years-worth of documents, articles and other more private archive material, this is a case where rarely is anything as it first appears, so what was I to think of the prospect of this lift? If a woman was behind the wheel tonight as well as a man – or instead of a man – did that really mean anything definitive in terms of my being able to be sure that I wasn’t getting involved in something I was going to regret?

It was another question that hung in the air. This case seems to have no end of questions that just hang in the air.

And I was about to hear another two, in quick succession.

“Well? You coming or not?”, Fiona asked again. I could see she was keen to get a move on, understandably. She had already been stranded in Larne long enough.

It was the last thing in the world I would do.

On the spot I consulted my gut. The night had seen enough strange and curious twists for one more strange and curious twist to seem likely. Either option carried a degree of risk. But the same buccaneering spirit I share with Inga prompted me to go with my gut and accept the lift. Inga presumably also trusted her gut feeling the night she accepted the same offer of a lift in the same place, supposedly to the same place. And look how that f**king turned out.

But when I thought of saying no, I knew that would mean missing out. Not just missing out on potentially getting to Belfast tonight, and having to spend the night on my own in arguably the creepiest ferry terminal in the world (it has to be remembered that Inga’s is the only such case in history, anywhere. No one else has ever been murdered straight after getting off a ferry and entering a ferry terminal. No one, anywhere. So if you were handing out awards for the creepiest ferry terminal in the world, Larne would be picking up the trophy with no other competitors even in the running).

But again when I thought of saying no, I knew I would be missing out – missing out on being one step closer to knowing. One step closer to learning. One step closer to whatever it was that I would discover by saying yes. If I said no, I knew I would be spending the night sleeping on the floor of Larne ferry terminal, and I would be learning nothing more than what that would involve. And I would never know what would have happened if I took the lift. And call me crazy, but I simply could not live with the thought of never getting to know what lay on the other side, no matter what might happen. I was willing to take the risk, even if only to be one step closer to knowing.

Chapter 91: A Lift from Larne

Under electric lights

I’ll go into the night, into the night

She and I

Into the nightSuede – ‘Still Life’

We walked through the doors of Larne ferry terminal and out into the cold night air. Just like inside the empty terminal building, outside there was nobody around. Suddenly I saw lights approaching. They were getting larger, twinkling ever wider and ever brighter. They were the headlights of a car. We walked towards it, the car pulled up and I moved towards the back of the car where I lifted my rucksack off my shoulders and prepared to place it in the boot. Again, I could not believe that this was happening, given the circumstances. “It was, and still is, unbelievable”, to quote Almut Hauser regarding the strange circumstances of Inga’s initial disappearance and subsequent death. I know it had been my intention to retrace Inga’s footsteps as accurately as possible, but this was ridiculous.

I climbed into the back of the car and took my phone out, the brightness of its screen a sole shaft of light amid the darkness of the car. Immediately I saw that I had just received a message from, of all people, one of Inga’s schoolmates who has become a friend of mine and who knew I was retracing Inga’s steps right then. Sitting in the back of the car while it was still parked in front of Larne ferry terminal my eyes scanned the message she had sent. The message read:

Now your journey will continue, and you will go where Inga wanted to continue her journey. You are completing her journey more than 30 years later.

Beautiful.

Only someone who had known Inga could type those words and have them carry as much weight.

However, I had not had time to post any new updates since getting off the ferry so at this point Inga’s schoolmate was still under the impression that I was intending to catch a train to Belfast. She had no idea that in what was possibly a moment of madness I had since decided to take a lift from Larne.

Suddenly the car began to move. I sat there in silent bewilderment as we drove off, leaving the Port of Larne behind. Soon we were on a main road, heading towards Belfast. Or were we? Where were the road signs? It was dark, and the car was moving fast. There were two people in the front of the car, one of whom I had never met in my life and the other who I had only met during the past few minutes on a railway platform. With my having never learned to drive never mind not owning a car, and possessing a questionable level of geographical awareness at the best of times, I wasn’t sure where we were, nor where we were going. I was strangely calm though. As eerie and intense a night as it had been, I figured that if things were to take a turn for the worse then at least I’d be an even further step closer to knowing. The experience felt like a strange kind of gift, a portal to a level of insight I would not have been able to have access to otherwise.

Suddenly Fiona and the driver began chatting and the mood in the car grew more jovial, and this continued even after I revealed to them why I had ended up in Larne in the first place and why I was looking to go to Belfast and then onto Dublin. I told them about Inga, and about retracing her steps. Neither of them had ever heard of her. I told them about the special and beautiful person she was, and how her entire life had been stolen from her in such horrendous and bizarre circumstances. Sometime later we were on the outskirts of what I belatedly recognised as the approach towards Belfast, and they told me they were going to drop me not only in the city centre but were taking the trouble to drive me all the way to the door of the youth hostel I planned to stay in in Belfast that night. How kind of them. I was so touched by this, and yet it made me feel guilty. Why was this happening to me but in the very same situation it hadn’t happened to Inga?

Then something amazing occurred to me. On the night Inga arrived in Northern Ireland off the evening ferry from Scotland she had every intention of catching the train from Larne to Belfast, and yet she hadn’t made it onto a train, and accepted a lift instead. And on this night that I had arrived in Northern Ireland off the evening ferry from Scotland I too had every intention of catching the train from Larne to Belfast, and yet I hadn’t made it onto a train either, and had also accepted a lift instead. But now it suddenly dawned on me that it didn’t matter that I hadn’t made it onto the train, that this did not hinder my mission to complete Inga’s journey after all. It actually made it even more special. Because due to the curious turn of events, I was now making my way to Belfast via a road vehicle. It meant that by accepting the lift from Larne ferry terminal and actually making it to Belfast by car, I was getting to honour her intended path even more accurately and faithfully than if I had travelled from Larne to Belfast via the train that it had been my and her original intention to catch! Because while it had been Inga’s (and my) original intention to catch the train from Larne to Belfast, this plan had been ditched at the last minute in both of our cases, by accepting the offer of a lift from Larne ferry terminal to Belfast in a road vehicle instead.

It was such a bittersweet moment, a realisation in both senses of the word. I felt relieved and simultaneously guilty. Guilty because although Inga’s and my plans had both run without a hitch until we separately reached Larne, only I had gotten lucky after leaving Larne, whereas she had been unbelievably unlucky. Why had I been spared, and she been spurned? It wasn’t fair.

But then I remembered the song ‘Vincent’ by Don McLean, that I consider one of the most beautiful songs ever written, and a song I think Inga would have loved (Inga was a folkie, and ‘Vincent’ is a folk song all day long, its gentle acoustic feel and mellow melancholy mood I am certain she would have at least liked. What’s more, considering it was written about Vincent Van Gogh, an artist, like Inga herself, and is the only hit song in existence to have been written about painting as an artform, about the artistic process and Van Gogh’s futile struggle to be received by the loveless and uncomprehending masses who failed to recognise let alone appreciate his genius during his short lifetime, I suspect she would have loved it).

And there is one line in this song that can be said to apply to Inga Maria Hauser every bit as much as Vincent Van Gogh – “This world was never meant for one as beautiful as you”.

Inga Maria Hauser

May 28th 1969 – April 6th 1988. Never forgotten.

_____________________________________________________

Copyright: Keeley Moss ℗&©2020. All rights reserved.

————————————————————————–

Acknowledgements for Part 34

Nowhere written by Bell/Colbert/Gardener/Queralt. Published by EMI Music Publishing © 1990

Something Must Break written by Joy Division. Published by Fractured Music ©1979

Still Life written by Anderson/Butler. Published by Kobalt Music Publishing Ltd., BMG Rights Management, Warner Chappell Music, Inc ©1994